Let’s Talk About Bullying

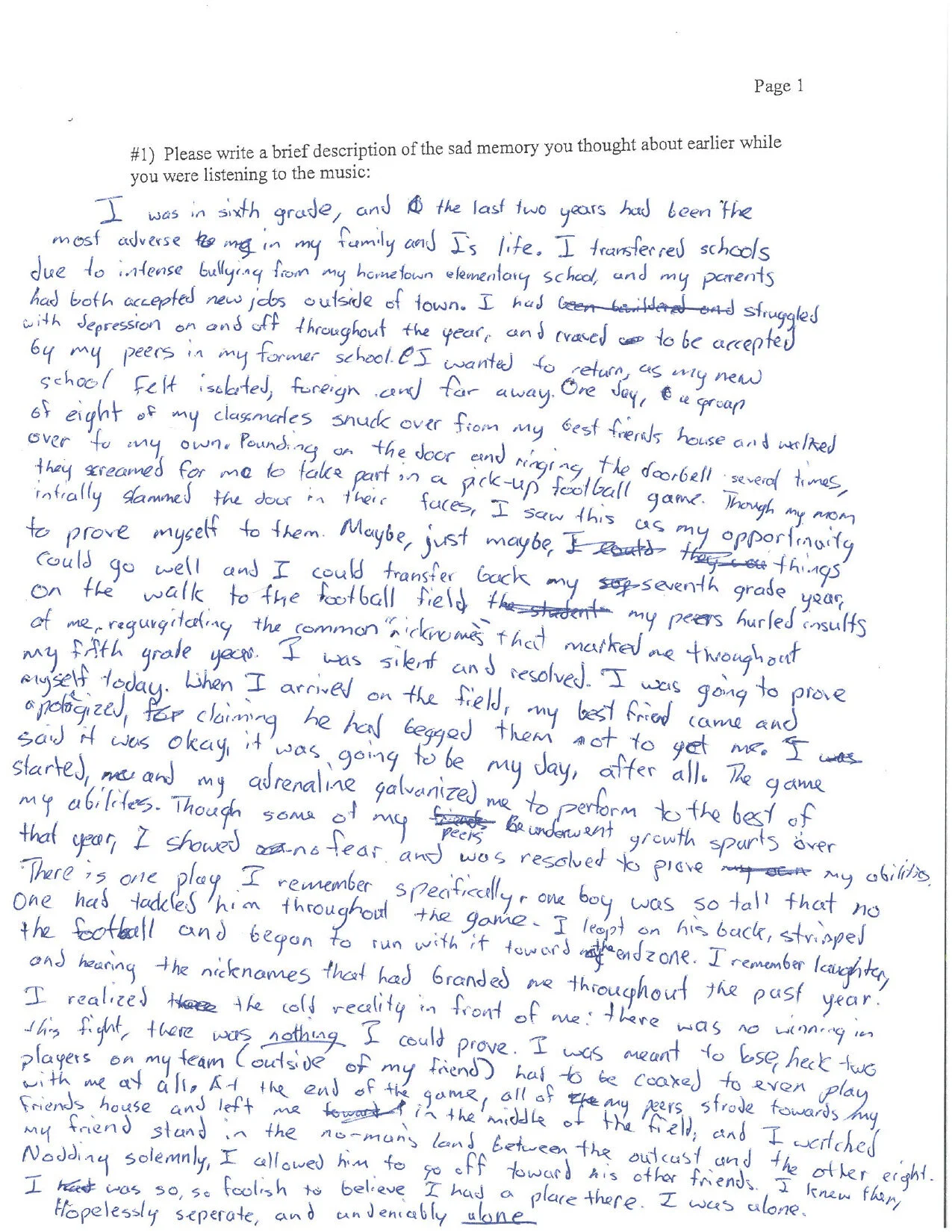

This photo, taken by my aunt, Jackie, captures one of the lowest times in my life.

February 6th, 2005.

It was the day the Eagles played the Patriots in the Super Bowl. I will remember the moment forever. I was lying on a waterlogged football practice field. I was alone, and I watched 7 of my peers taunt me, throw slurs at me, and abandon me on the field. My voice was stripped away, and I have never forgotten what that felt like. The following text is adapted from an assignment I had to rewrite a dark memory in a psychology class. In that class, I did not feel fully comfortable sharing some of the details of what happened in that day – but I have attached a copy of the original text at the end of that post.

The Game

I was in 6th grade. The last two years had been the worst two years of my family and I’s life. I transferred schools due to intense bullying from my hometown elementary school, and my parents both accepted new jobs out of town. I struggled with clinical depression throughout the year and had unhealthy coping mechanisms. Beyond anything else, I craved to be accepted by the student’s of my old elementary school. The previous year, the common thing I heard through the school was that bullying “did not happen” in my school. That had not been my experience, but messaging like that was difficult for me to process at 11 years old. It was common to hear things like “we had a tight-knit culture” and while “other” schools might have that problem, bullying wasn’t present here. If bullying did not happen here, then was I the blame for my own treatment? Was I myself to blame for what was happening to me?

Despite everything. Despite getting pulled out of this school after my 5th grade year, I wanted to return in 7th grade. My new school felt isolated and far away. My best friend from my hometown was having a party, it was around his birthday, and had invited six of his classmates to the party. He suggested that they would not treat me well if I was invited, so I did not get an invitation – which I understood.

The six friends came over to my house anyway. They pounded on my door and rang the doorbell several times. They kicked over my bike outside and asked me to play in a pick-up football game. My Mom slammed the door in their faces, and I could hear their laughter outside. I wasn’t deterred, though – this was going to be different. This was my opportunity to prove myself to them. Maybe, just maybe, I could play so well, earn their acceptance, and transfer back to my hometown school for my 7th grade year. When I was walking to the field, they all walked behind me. Taunting me and saying they were “talking behind my back just like last year”. They hurled insults at me, repeating the ones they most often used the previous year, g**, f****t, and slurs of my last name. I was silent and resolved. I was going to prove myself today. When I arrived on the field, my best friend ran up and apologized, claiming he had begged them not to go to my house. I was it was okay, it was going to be my day.

When we were picking teams, only my friend volunteered to play on my team. No one else wanted to do it. I got a flashback to the previous year where one of my classmates at recess said “If anyone wants off Ben’s team, join mine.” Everyone left.

I was worried this was going to happen again, but they made two other players join my team so it was even. The game started, and I was playing the best that I could. I was resolved to prove myself to them. I was short, slightly chubby, and physically outmatched by a couple of players who had growth spurts over the summer – but I played like it was the most important game of my life. I will forever remember one moment in this game. One boy was so tall that almost everyone else was afraid to tackle him. But I saw my moment, I leapt on his back, stripped the football and began to run to the end-zone. I remember laughter. Everyone had stopped playing and were pointing at me, calling me the same names that had branded me in the past year. I realized in that moment that I was never in this game at all – I was the game. There was nothing I could prove. Everything about me had already been written the previous year, and there was nothing more I could write. Soon after I slipped and fell on the cold grass. They pointed, laughed, and left me in the middle of the field to go back to my friend’s house. As they walked away, I watched my friend stand in the middle of us, the no go zone land between the outcast and his classmates. I nodded solemnly, and he too left to party with his other friends.

I came into the game thinking it would be one of the most important in my life, a chance for me to prove myself for others. In a way these naïve ambitions were painfully correct and tragically wrong. The game proved who I was to them, and allowed me to realize that going back to my hometown school would never allow me to find the person I wanted to be. I never forgot the feeling of losing my voice, and the day made me resolved to help give others a platform in this world.

Soon after this game, I took my Dad’s advice and started writing as a way to sublimate the anger I felt through my elementary school life. The most difficult part of it was being told by adults I respected that my experiences with bullying were “exaggerated,” “didn’t happen” or just a “part of school” and that I needed to “toughen up.” I remember watching The Breakfast Club in middle school and feeling a strange, conflicting set of emotions after it was over. I realized I wanted to write a novel that was set in a high school, one that featured a vast array of characters who were all part of the pseudo-societies created inside school. But I felt conflicted about how The Breakfast Club ended. It felt like everything I watched would be reset to 0 the moment school started back up again on Monday. In many ways, the cynical part of me felt like that would have been a more powerful and realistic ending, a shot of the school day on Monday, and nothing had changed in that system. All of the characters would be swept away by the social order in their school and regress to that mean. I found that story later. It was when I read The Chocolate War by Robert Cormier when I realized exactly what I wanted the book to say. This quote from the book has hung with me since the day I read its powerful resolution.

Jerry Renault, the main protagonist of Robert Cormier’s The Chocolate War takes part in a school boxing match at the end of the novel (Scroll down to avoid Spoilers).

“Triumphantly, he watched Janza floundering on weak, wobbly knees. Jerry turned toward the crowd, seeking-what? Applause? They were booing. Booing. [...] that crowd out there he [Jerry] had wanted to impress? To prove himself before? [...] they wanted him to lose, they wanted him killed, for Christ’s sake. ”

Similar to how it did not matter I played on that rain soaked practice field, Jerry comes to a similar conclusion. And in Jerry’s case, his assistant principal knew full well about the boxing match, but wanted Jerry to “learn a lesson” because he refused to participate in the school’s events. Jerry, in the eyes of his institution, deserved everything that was coming to him.

This crystallized the book I wanted to write. I wanted a book that didn’t pin the blame on the abusers in school, but the system that allowed and encouraged the abusers to thrive. While I never did return to that school district, it only took two years for me to make amends with every single one of my peers that shared the practice field with me that day – but those scars will always remain – and those scars were caused not by them, but the system we all relied on. I think of the adults who told me that I was “making up” these stories, the adults who told me that I “needed to toughen up,” and the adults who saw these things happen, but choose not to intervene or even let my parents know what was going on. Truth be told, I don’t have any lingering resentment towards the adults in this situation either, what I’ve realized through reflection and through therapy was that I was in a system that simply did not have space for what I was going through. The adults I remember who saw exactly what was happening were also at the whims of a system that did not even consider that a story like mine was real. Heck, how can a school admit that bullying is happening when the school’s message is that “bullying does not happen here”? Just admitting that my situation was happening would be challenging the school’s very messaging - and at worst, be saying that school was promoting a lie. While I feel happy that I made it out of that situation, there are too many students that aren’t – and this book, Bleak, is for them.

To all of the people who are stranded on their own rain soaked practice fields, it is my deepest hope that this book provides a small light in your world.

Original Journal Entry - written in a psyc class a few years after the event.